United Auto Workers union President Shawn Fain joins striking UAW members on the picket line at the Ford Michigan Assembly Plant, Sept. 15 in Wayne, Michigan. (OSV News/Reuters/Rebecca Cook)

CNN ran a story by John Blake last week about Shawn Fain, the leader of the United Auto Workers, and how he was deeply influenced by his faith. The article gave a short history of the Social Gospel and seemed somewhat surprised that there was still any such thing as a left-leaning iteration of the Christian faith. I was reminded of the headline The Washington Post gave to a story back in 2008: "The Religious Left? Is nothing sacred?!" I remember that headline well. Click on it and you'll see why!

The ambivalent situation of the Christian left is another story for another day. But there were two things that were interesting about the CNN story. First, there was a complete absence of any information about the Catholic Church's history with the trade union movement and, second, the inability to see why the labor movement and the Christian faith were natural partners. Perhaps supernatural partners too.

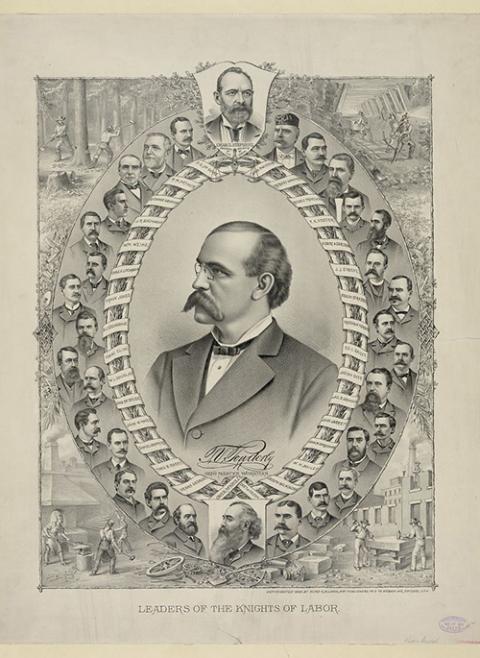

Blake only mentions one Catholic in his piece, Dom Hélder Câmara, whom Blake misidentifies as a "Brazilian theologian" when he was an archbishop. It is also strange that Blake fails to mention Walter Rauschenbusch who was the leading theorist of the Social Gospel movement in the 19th century. But while our Protestant brothers and sisters were birthing their Social Gospel movement, Roman Catholics were busy starting unions. The Knights of Labor, though founded by a Quaker, grew to prominence under the leadership of a Catholic layman, Terrence Powderly.

A lithograph print titled "Leaders of the Knights of Labor" features Terence V. Powderly, "Genl. Master Workman", bust portrait, facing left, within a wreath. Clustered around the sides of the wreath are 30 bust portraits of other labor leaders. (Library of Congress)

The Knights of Labor had to conduct their meetings in secret because employers were keen to expel members from their factories. At that time, "secret societies" were still a cause of great concern to the Vatican, mostly because of Freemasonry. (Apparently, it is still a concern at the Vatican!) At the prompting of Canadian Cardinal Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, the archbishop of Quebec, the Holy See condemned the Knights of Labor as a secret organization.

American Cardinal James Gibbons, however, drafted a memorial letter to the Vatican, asking that the ban be lifted. The cardinal of Baltimore also wrote a letter to the Knights, to be read at their convention, hoping to increase their numbers. In the end, the Vatican said that membership in the Knights could be tolerated, but the proto-union was already in decline. The far more significant consequence of the back-and-forth was the effect on the thinking of Pope Leo XIII who, in 1891, wrote the Magna Carta for Catholic social teaching, Rerum Novarum.

Throughout the 20th century, labor priests were active, bringing Catholic social teaching to rank-and-file workers. Msgr. George Higgins' long service as chaplain to the AFL-CIO was honored last year with a panel and a special Mass. Popes continued to teach about the right to organize. The U.S. bishops filed an amicus brief supporting the right to unionize in the Janus v. AFSCME case and bishops are frequently key in defeating anti-union legislation, as happened in New Hampshire in 2021.

Why does it make sense that organized labor was born in the bosom of Christianity in this country? It is true that Protestantism and the Enlightenment introduced a strongly individualist and subjectivist understanding of the claims of the Christian faith. But a plain reading of the texts of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures evidences a more communitarian understanding of ethics and belief.

Advertisement

Ancient Israel was, for all intents and purposes, a theocracy. God's law dictated the organization of Israelite society and set forth prescriptions and proscriptions for both individuals and society. Only modern, ill-informed, exegetes, people like House Speaker Mike Johnson, think that Yahweh's commands to care for the widow and the orphan, and to welcome the stranger, and to leave the gleanings of the harvest for the poor, were invitations to personal charity. They were laws for society as Mark Silk explained at Religion News Service.

Christ preached a demanding ethic of personal conversion but he also proclaimed the reign of God. He not only confirmed the law of Moses, he ordered his apostles to preach the Gospel to all nations. As then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger said in the introduction to the 1988 edition of Henri de Lubac's Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man: "The idea of community and universality … permeates and shapes all the individual elements of Faith's content."

So, when workers in the very religious 19th century looked for metaphors and ideas about the solidarity they know they would need to succeed in organizing themselves into unions, it was only natural that they turned to the same verses and ideas that shaped the Social Gospel and Catholic social teaching back then and formed Shawn Fain and millions of religious progressives today. There is no group in American society with whom it is easier to share a conversation about Catholic social teaching than the leaders of the American labor movement. It is my experience that the concepts drawn from papal teaching are always received on the first bounce among labor folk. They get it. They live.

No one should have been surprised to read about Fain's faith. As the labor movement finds new strength and support in American society, the leaders of the Catholic Church, clerical and lay, would do well to stand arm-in-arm with organized labor. Fighting together for a more just society is our heritage and our hope.